I mean, for anyone following the story, it was only a matter of time before I got around to analysing The Sentinel and giving it "the treatment".

I started my Geoff Crammond journey in 2021 when I disassembled and documented Aviator, his epic Spitfire flight simulator that came out on the Acornsoft label in 1984. This was only his second commercially released game; the first, Acornsoft's Super Invaders, was an excellent version of the arcade classic, but it was still a relatively straightforward game. Aviator is anything but straightforward; it simulates a whole world using genuine physics and an awful lot of maths. It was a pleasure to dissect and discover, especially as nobody had published any information on the game's code prior to my project.

After enjoying Aviator so much, it was a no-brainer to move on to his next game, the epic 1985 Formula 3 driving simulator, Revs, which I disassembled and documented in 2022. Revs is much more complex than Aviator and it was a serious challenge to pull it apart, as again there was nobody whose work I could reference. It remains one of my proudest disassembly achievements.

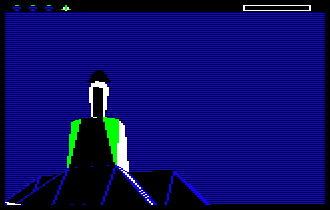

For his fourth game, 1986's The Sentinel, Geoff Crammond went completely off-piste. Gone is the applied mathematics of Aviator and Revs, and instead The Sentinel is all about pure mathematics; while Aviator and Revs are very much grounded in the physics of the real world, The Sentinel is vectors and trigonometry and arithmetic and the cold, hard logic of robots inhabiting eerie and otherworldly landscapes. The core maths routines in The Sentinel are carried over from Revs, as is the equirectangular projection system that enables the clever filled-3D landscape to work, but the rest of this game is utterly unique.

It's like a VR game from decades before VR became mainstream, using the limitations of 8-bit technology to create a deeply unsettling and atmospheric experience. I believe the original idea that sparked the game was to write a real-time 3D engine, and it was the hardware limitations that resulted in the stepped scrolling that makes the game so brilliantly tense. It's a great example of constraints creating art, but having looked at the code, I suspect Geoff Crammond spent a fair amount of effort making the underlying routines as efficient as he could before settling for the staggered panning approach. It is, as you would expect, beautifully written.

I just had to take it apart, and I hope you enjoy the results as much as I enjoyed documenting them.